About the Author

Kerry Nguyen-Long's History with Vietnam

Born and educated in Tasmania, Australia, Kerry was awarded an Arts Degree at the University of Tasmania followed by a Diploma of Education. Her interest in Vietnam began following marriage in 1966 to fellow student Nguyễn Kim Long from Vietnam, recipient of a Colombo Plan scholarship, but in Australia, there was a dearth of information on the arts and culture of the country which, at that time, was experiencing an agonising war. Meanwhile Long’s (aka Kim) employment took the family to Canberra and in 1975 to Papua New Guinea where Kerry taught at St Joseph’s Catholic school. Four years later, with four young children, the family moved to the Philippines, and it was here as a member of the Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines that she encountered Vietnamese ceramics, exported to the Philippines in the fourteenth-fifteenth centuries. At that time little was known about them but for Kerrry it opened the first door into Vietnam’s fascinating past. Meanwhile as a member of Museum Volunteers of the Philippines Kerry worked in different museums as a catalogue author, undertook an intensive course in Philippine history, and for a short time worked as a guide at the Ayala Museum, in Makati. Under this volunteer organisation she worked on the stoneware jar collection in the National Museum of the Philippines and went on to co-author a book titled A Thousand Years of Stoneware Jars in the Philippines. This was published in 1992. To assist in the categorisation of the more than 150 jars selected for publication, Kerry devised a typology which featured in a section titled “Typology and Classification”.

When, in 1986 the Vietnamese government introduced their reform policy đổi mới (renovation) it was much easier to visit family, and to visit cultural sites, and artisans at work, and importantly easier to make meaningful contacts with Vietnamese professionals working in the arts. Early research saw her contribute a short essay to the book Bát Tràng Ceramics 14th-19th Centuries by Professor Phan Huy Lê, Nguyễn Đình Chiến and Nguyễn Quang Ngọc published in Vietnam in 1995. Several years later she co-authored with Bùi Minh Trí the book Vietnamese Blue and White Ceramics published in Vietnam in 2001. Kim translated both these bi-lingual books as well as others, including museum catalogues such as that for the Vietnam Museum of History in Ho Chi Minh City, titled 365 Steps Inside the Museum of History, published in 2012. His interest has assisted Kerry in her research. In the early 1990s she was able to relocate to Vietnam to pursue language studies.

In 1999 she was invited to be a contributing editor of the international magazine Arts of Asia and has since written many articles for this magazine on Vietnam’s visual culture, with Kim taking on the role of dedicated photographer. They now have a large library of images dating from the nineteen seventies.

During her years of research Kerry became acutely aware Vietnam’s arts were a neglected area rarely encountered in English language publications and furthermore there was a tendency for its arts to be disparaged. She came to understand this was consequence of insidious entrenched thinking traceable to the nineteenth-century political rationale mission civilisatrice. The engendered thinking was that Vietnam’s visual arts were a pale imitation of that of China. Such thinking is encountered in English language museum catalogues, and book reviews. Books on the arts of Southeast Asia often omitted Vietnam or, if included, dismissed its arts with breathtaking brevity. She felt compelled to address this issue and hopes her research and writings have contributed to deeper understanding and more balanced perspective. Towards this end she travelled extensively throughout the country, gaining firsthand knowledge of historical sites and structures, researching artifacts in museum and private collections, conversing with Vietnamese experts, and together with Kim photographing, recording and researching papers published by Vietnamese scholars. The accumulated knowledge from this research resulted in her first book, Arts of Việt Nam 1009-1945, published in 2013, and commended in the Australian Arts in Asia Awards in 2013.

Kerry served a term as a committee member of The Asian Arts Sociey of Australia (TAASA). In 2002 Kerry was a guest editor of the society’s magazine TAASA Review, in an issue on Vietnam (Vol. 11). She also conducted a workshop on ceramics recovered from the Cham Island site prior to auction in San Francisco in October 2000. She is currently a member of TAASA, Asia Society Australia, and Foundation and Friends of the Botanic Gardens.

Selected Snapshots from a Journey of Ongoing Research

On Ceramics, Collectors and their Collections

With her knowledge of centuries-old Vietnamese ceramics Kerry has written numerous essays on this subject. During a period living in Huế Kerry and Kim befriended Huỳnh Văn Chuẩn, owner of a tiny shop selling a mix of objects, mostly old, from ceramics to paraphenalia left behind by Americans soldiers. Chuẩn had acquired an interesting ceramic collection. Strolling in the cool evenings along the riverbanks he had noticed old ceramics tossed aside from barges which had off-loaded sand dredged downstream near the ancient Thanh Hà port in the Hương River; this sand was to be used in the burgeoning urban constructions which followed the 1986 renovation policy. Chuẩn knew these ceramics were old because in the years before 1975 he had worked as an assistant in an antique shop in Saigon. The ceramics dredged up in the sand had been lost centuries ago and although most were damaged a surprising number were in good condition. These ceramics were the genesis of Chuẩn’s ceramic collection and this encounter with him led to a 2005 illustrated essay titled “Vietnamese Ceramics: A Cameo Collection from the Sands of Time,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 35, No. 3, May-June 2005.

In 1997 she wrote an article on the closed ceramic limepot, peculiar to Vietnam, although an open limepot is also favoured in the south. Approximately one third dry slaked lime is placed in the pot followed by one third water, the remaining space allowing for effervescence. The resulting paste is removed with a small spatula and placed on a betel leaf, together with several other ingredients. This is neatly folded to form a tiny package – the betel quid. In the past this was offered in social exchange. This was a custom common to many countries in Southeast Asia, each country with its own distinctive paraphenalia. In Vietnam the limepot and the quid was referenced in folk songs and political commentary. During her research she was introduced to knowledgeable collectors. See “Vietnamese Limepots’ Arts of Asia, Vol. 27, No. 5, Sep-Oct 1997.

An essay published in the Australian magazine Ceramics Art and Perception Issue 23, 1996, featured Bát Tràng master potter Lê Văn Cam, born in the ancient ceramic village in 1930. At that time Bát Tràng was still a quaint village not yet touched by modernism, and as Cam had remarked of its laneways “so narrow a coffin couldn’t be turned”. He grew up without the benefit of material comforts, and at age 13 worked in one of the village kilns but in 1950, aged 20, during war against the French Cam lost a leg. He would eventually return to work in ceramics and developed an interest in researching and reproducing historical forms and experimenting wi†h lost glazes; in 1987 he was awarded a gold medal for the reproduction of a Mạc dynasty (1527-92) altar lampstand with crackled fungus-green glaze. He was inspired by significant lampstands made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by renowned potters for use in pagodas and communal halls; many are inscribed with details about their making, including date of making, and name of ceramists and survive in village pagodas and communal halls (đình) into the present. Cam also began to use the dragonfly motif on rice bowls, a motif featured on Vietnam’s ceramics exported to Japan in the seventeenth century and now a popular motif on contemporary Bát Tràng ceramics. A cheerful generous man with a dry sense of humour Cam patiently explained much about ceramic making. Encounters such as this led Kerry to research deeper into Vietnam’s past and explore the cultural context of different artistic endeavours. The author has visited Bát Tràng on numerous occasions.

In 2003 Tuyết Nguyệt, founding editor of the Arts of Asia, invited Kerry to write on a private ceramic collection in Indonesia. This was a significant collection comprised of heirloom ceramics, imported into Indonesia from Vietnam in the fifteenth century. Generally, ceramic collections acquired within island Southeast Asia in the mid decades of the twentieth century had been purchased from dealers who had in turn acquired them from unauthorized diggings. For such acquisitions their cultural or historical contexts were lost. This unregulated phase of early ceramic collecting in Southeast Asia is described in the essay “A Record of Vietnamese Blue and While Ceramics in Export Contexts” in the book Vietnamese Blue and White Ceramics co-authored with Bùi MinhTrí, published in 2001 by Social Sciences Publishing House, Hà Nội. The anonymous Indonesian collector had purchased his ceramics from traditional owners and the cultural history for some are well documented, a fact which adds value to the collection. They include, for example, a dish with a red painted fish swimming among green and red plant forms once used in the pre-wedding ceremony known in Buginese-Makasarese as Mapaci. This dish held the leaves of the karuntigi plant, bruised to exude a red substance, and in the ceremony each guest would take up some of this and rub it into the bride’s palms leaving a red mark as a symbolic gesture wishing her wealth and good fortune in married life. A tazza in the collection although worn by centuries of handling still showed traces of gold overglaze. Some commentators had doubted this gold was old, suggesting it was a recent addition but documentation of fifteenth century ceramics recovered from a shipwreck discovered off the coast of Vietnam near Hội An, excavated between 1997 and 1999, included significant numbers of ceramics with the same type of gold overglaze. The Indonesian heirloom collection is described in the 2004 Arts of Asia essay, “An Indonesian Collection: Vietnam’s Painted Ceramics.”

On the Cham Island Shipwreck Site

The sunken vessel referred to above, located off Cham Island near the popular tourist town of Hội An was discovered when a fisherman’s net was snagged. This was big news in Vietnam and among Asian ceramic specialists. Excavations which extended from April 1997 to July 1999 eventually recovered 150,000 intact ceramic artifacts made in Vietnam and the evidence they provided discarded long held inaccurate views about the dating of its painted ceramics. Kerry wrote on this subject in “Treasures from the Hoi An Hoard: Vietnamese Ceramics and the Cham Island site: Significance and Implications,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 31, No. 1, Jan-Feb 2001. A large part of the recoveries was subsequently sold at Butterfields Auction House in San Francisco in 2000. However, the sale was advertised as “Important Vietnamese Ceramics from a Late 15th/Early 16th Century Cargo”, a dating that was both premature and inaccurate and subsequently led to a great deal of confusion.

An essay titled “Trade and Exchange in the Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries through the Prism of Hoi An”, focusing on that town and its long history as a trading port also describes types of ceramics recovered from the Cham Island site. It features in the publication Arts of Ancient Vietnam from River Plain to Open Sea by Nancy Tingley, published in 2009 by Asia Society and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA and distributed by Yale University Press. Kerry has also written about this in an extensive essay on the Yi-Lu Ceramic Collection, “Vietnamese Ceramics: in the context of history, religion, and culture”, in the 2016 book Vietnamese Ceramics from the Yi-Lu Collection.

On Woodcore Lacquer Statuary

Most statuary made in the earliest dynasties is lost although some are known through old texts. By comparison statuary dating from the sixteenth century is comparatively numerous and include portrait statues of lay donors who were readily admitted into pagoda precincts. Some are introduced in the essay “Portrait Statues from the 17th-18th Century Vietnam,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 42, No. 6, November-December 2012. For many years Kerry researched lacquer as a medium used in conjunction with woodcore and clay statuary. The essay “Statue-Making in Northern Vietnam from Stasis to Regeneration,” Arts of Asia, Winter, 2021, describes the regeneration that followed the depressed state of the craft during the time of agricultural collectivisation. Her illustrated essay describes the various steps in the making, from the wood or clay core to the time-consuming and exacting lacquering process. Today a new energy is evident as Vietnamese artisans create beautiful statuary for the twenty-first century generation.

On Silvercraft

Vietnam’s silvercraft is relatively unknown outside the country but there are many living artisans, progeny of past generations who had worked in guilds, producing beautiful quality wares. Typical is the family of Nguyễn Ngọc Khuông (1929-2017), silversmith, teacher, and Golden Hand awardee (April 1990). This family holds artifacts created by four generations. In their home village Kerry was able to examine artifacts made by past members of the family. An essay on this family titled “Silvercraft in Vietnam: Four Generations” features in Arts of Asia, Vol. 32, No. 3, May-June 2002.

On Interviewing Contemporary Artists

Kerry has interviewed and documented contemporary artists, mainly an older generation. They include Trần Lưu Hậu (1928-2020), Trần Nguyên Đán (“Tran Nguyen Dan and his Woodblocks,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 33, No. 6, Nov-Dec 2003), Mai Long and Phùng Phẩm. She has kept in close touch with Trần Nguyên Đán, and he has educated her about different aspects of the craft.

For her essay on Nguyễn Tư Nghiêm (1918-2016), “Nguyen Tu Nghiem: One Man’s Journey into Modern Painting,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 37, No. 6, Nov-Dec 2007, she could not secure a personal interview due to the artist’s health issues. Kerry first saw a woodblock by artist Phùng Phẩm hanging in the Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum and later came across a small black and white publication featuring his work. This convinced her she needed to seek him out. Subsequently she had several long interviews with the artist who initially focused on woodblock but, who after 1986, turned to lacquer.

She interviewed Lưu Công Nhân (1931-2007) in his studio in Dalat only a few months before his passing. Nhân was very keen to show his many paintings, some hanging on walls, others stored in boxes, and described in detail circumstances that inspired each. It was a balmy day and for a time they sat outside his studio; a full banana bud was hanging on a nearby plant and although suffering from advanced Parkinson’s disease he sought ink and brush, sketched the bud, added a dovecote, and then wrote a dedication. He gifted her a book; inside he inked a woman’s head and wrote a dedication. This recollection is one of her many personable encounters.

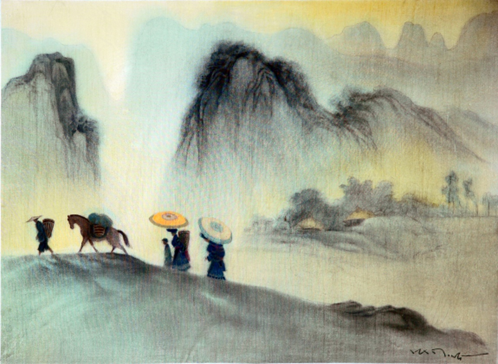

An exceedingly pleasant afternoon was spent with silk artist Mai Long as he fondly reminisced about his childhood and summer days hiking as a boy scout, and from the 1950s his days studying in the Resistance Art Class in Việt Bắc (Northwest Region); he recalled the many hardships; the comraderie among students; and living among minority people. Access to art materials back then was a problem. The artist laughed heartily at recalling how when a visiting lecturer arrived on horseback, some students, without permission, cut off a generous length of the horse’s tail to provide material for painting brushes and the subsequent dismay of the lecturer on seeing his horse with a bare dock. This interview yielded valuable insights into a personal experience in Việt Bắc . Mutual friend Nguyễn Bích, also present, similarly enjoyed the reminiscences. See “Vietnamese Silk Artist: Mai Long,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 37, No. 3, May-Jun 2007.

Writing About Excavations

There have been significant excavations during the years Kerry has been writing. The Cham Island shipwreck site, described above, was very important as it provided an approximate date for the site and set aside long held misunderstandings on the dating of glazed and painted Vietnamese ceramics of the type recovered. The Ba Đình excavations at the Thăng Long Imperial Citadel in Hanoi cover 19,000 square metres and reveal each successive dynasty layer by layer from the time of Chinese domination in the 7th to 9th centuries right through to the Nguyễn Dynasty (1902-1945). The recovered materials inform on town layout, location of palaces, architectural embellishments, and ancient road alignments. Vast quantities of building materials were uncovered along with brick-lined wells, artifacts associated with defence, and insights into the lives of members of royalty, from their fine blue and white ceramics to lakeside pavilions and shallow bottomed boats used for pleasure. The data from this site served to verify, modify, and correct previous understandings. Kerry considers it fortuitous she could write on such sites with their important historical findings. See “Ba Dinh Excavation: Thang Long Imperial Citadel,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 37, No. 4, Jul-Aug. 2007.

Nam Định Provincial Museum

Nam Định is about 85 km south of Hanoi. Its new modern museum, Nam Định Provincial Museum, opened in 2005. Nam Định was the homeland of the Trần clan where they built a second capital. Excavations in the vicinity have yielded significant ceramics, dated bricks, and important architectural materials. Mt. Chương Sơn (present day Mt Ngô Xá), the site of the Chương Sơn Tower completed in 1117 is also located in Nam Định. Excavations at the site have yielded stone artifacts, some with beautiful carvings, testimony to the fact Lý pagodas were not only built on delta plains but also on mountain sites. Nam Định is also the site of the important Tran dynasty Pho Minh Pagoda and this province is the centre of the cult of the Mother Goddess Liễu Hạnh, who is understood to have lived between the years 1434 and 1473 in Vỷ Nhuế Commune, Đại An District, Nam Định. Linked to the ancient past and the country’s wet rice culture, the cult is today celebrated by many thousands in a rich and colourful tableau of rituals including possession by spirits, with dancing, music, singing, and the telling of legendary stories. UNESCO has recognised the cult of the Mother Goddesses as a component of Vietnam’s intangible culture. Director Nguyễn Văn Thư was always welcoming and generous in assisting with any research associated with Nam Định Province. See “Nam Dinh Provincial Museum, Vietnam,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 48, No. 1, Jan-Feb 2018.

Other Photos